Bean-to-bar is a term I used in many, if not all, of my videos, but its use is currently not regulated in the US. A bean-to-bar manufacturer oversees the chocolate production chain, from sourcing the beans to making the actual bars. Some may argue that a bean-to-bar chocolate-maker has to produce chocolate in small batches but there is no reason, in my mind, why the term should be associated with a specific production scale.

A bean-to-bar chocolate-maker will therefore be responsible for sourcing the beans before processing them through each of the following steps:

- Sorting

- Roasting

- Cracking

- Winnowing

- Grinding

- Conching

- Tempering

- Molding

If that sounds like a lot of work, it is because it is. The whole process takes days and when people ask me if I ever feel like making chocolate, all I have to do is referring them through each of these steps to help them understand that my answer is a big “no”.

The next question would be: how do you recognize a bean-to-bar chocolate? My answer: by checking the list of ingredients. A bean-to-bar chocolate bar will most likely list “cacao”, “cocoa”, or “cocoa beans” as its main ingredient. I took a picture of two ingredient lists on two different bean-to-bar chocolate labels so you could see yourself.

This is what you’ll find on the side of a piece of Woodblock Chocolate.

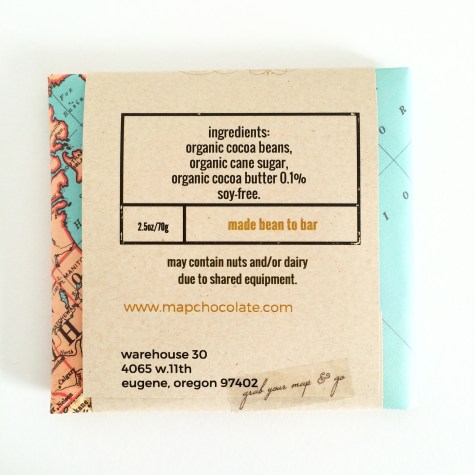

And here is the list of ingredients on a bar made my Map Chocolate:

OK, but isn’t all chocolate made from cacao beans? Technically, yes, but, it is not always made by the company whose name appears on the bar. As I mentioned in a previous post, a chocolatier uses already-made chocolate, typically referred to “couverture chocolate”, to use in his or her chocolate creations. I like to say that chocolate-makers express their personality by making chocolate and chocolatiers by making chocolate confections.

To spot a bar made my chocolatier, look for information on the wrapper. For example, CHUAO decided to claim its chocolatier status by indicating it on its wrappers.

Other times, you’ll have to do a little more work to determine whether the bar is made by a chocolatier or not. If the company uses couverture chocolate in its bars, it will likely NOT list “cacao” or “cocoa” in its list of ingredients but “dark chocolate” or “milk chocolate” as a first ingredient.

Now comes the trickier part. Some makers actually make chocolate from a product called “cocoa mass” or “cocoa liquor”, which is what you call cocoa after it has been ground and melted.

The whole idea of using cacao liquor to make chocolate is very puzzling to me. How do you become a liquor processor? Where do you find these companies? How do you ship that liquid product to a maker? If you have an answer, please feel free to chime in.

Identifying a maker that uses cocoa liquor can be easy, as you will see on this ingredient label.

Other times, you will have to study the label a little more closely. Check this label of Moonstruck Chocolate, for example. The first ingredient on the bar is “dark chocolate”, which is described to us as a mixture of “unsweetened chocolate, sugar, cocoa butter, and soy lecithin”. My interpretation of the label is that the chocolate is made in-house from cocoa liquor that has been melted and molded, mixed with the additional ingredients. In other words, the company probably has not sourced, roasted, cracked, sorted, winnowed, and ground the cacao itself.

Phew. Who knew interpreting a label could be that hard?

I hope this post helped you understand how to identify a bean-to-bar chocolate. Let me know of your questions or comments – I’d love to hear from you.

You can read the second part of the article here.

Did you like this article? If so, sign up to my newsletter to be notified of future blog updates.